Lesson in geometry, growth, and foundations of calculus

Alan Kay and computational thinking part 1.

This first exercise is fantastic and notably does NOT need a computer. Although my focus here is definitely about computation, computers are too often used just for the sake of the technology. Let's not use computers in the classroom unless they're adding something vital to the lesson. Dr. Kay credits Julia Nishijima with this lesson.

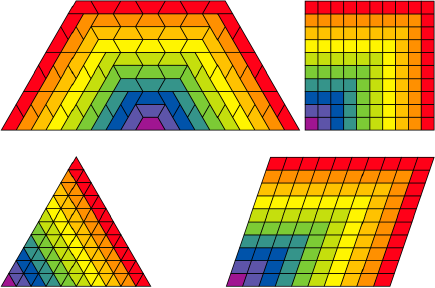

"The children pick a shape that they liked, and the idea was to, using just those shapes, make the next larger forms that had the same shape." [The Real Computer Revolution Hasn't Happened Yet p. 7]

They're asked to write down two numbers with each new size: how many tiles were added, and the total number of tiles. Later in the exercise they're asked to share their results with the class at which point they're stunned to learn that they all have the same table of numbers:

| shape | how many added? | how many total? |

| 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 3 | 5 | 9 |

| 4 | 7 | 16 |

| 5 | 9 | 25 |

| 6 | 11 | 36 |

| 7 | 13 | 49 |

| 8 | 15 | 64 |

| 9 | 17 | 81 |

| 10 | 19 | 100 |

Children generally notice the pattern in these series of numbers. The odd natural numbers on the left and the series of squares on the right. Kay points out that these are first and second order differential equations. I note specifically these equations:

f(x) = x2

f'(x) = 2x - 1,

With this exercise we have laid a foundation for calculus. We've revealed a little number theory: that the sum of the first n odd numbers is n2. We're only a few steps from describing infinite series of numbers. We could talk to the kids about why square numbers are called "square" and similarly with "square roots" -- these strange names betray geometric origins and we have the geometry right in front of us with this exercise. With a little creativity, we can also introduce functions. "I have a magic box. I put a number in on one side and the number that comes out the other side is the first number multiplied by two. I have another box which always subtracts one. What happens if I put these boxes together in a line? Let's try putting some different numbers in and see if there's a pattern." Given f(x) = 2x and g(x) = x - 1, g(f(x)) = 2x - 1. With elementary age kids we can maybe skip the formal notation until we've introduced them to the notion of a variable.